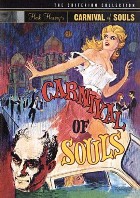

In reading professional and informal reviews of Herk Harvey's 1962 independent film Carnival of Souls, it becomes clear that one either "gets" this eerie opus or does not. I always have, ever since I was riveted to the television during an airing of the film when I was about six. In middle age, the film has no less profound an effect on me.

The story is not especially novel, though the treatment certainly is; it deals with material that also served as the thematic basis for later films like Jacob's Ladder (1990) and The Sixth Sense (1999) as well as numerous Twilight Zone episodes: "The Hitch-Hiker" (1960)--which was itself a 1940s radio play--especially comes to mind. The plot in brief: Mary Henry is one of three young women in a car when a foolish drag race against a car of young men ends with her and her companions in a river, their vehicle having been edged through the railing of a wooden bridge. Only Mary Henry emerges, with no memory of the accident. She is a professional organist and soon leaves for a church job in Salt Lake City. However, from the point of the accident, she seems strangely detached from her surroundings and experiences moments when she is not even seen or heard by other people; at these times, she feels that she has no place in the world. Moreover, she is pursued and terrified by the recurring image of a ghoulish figure (played by the director) that no one else perceives, and is strangely drawn to the ruins of the Saltair pavilion outside Salt Lake City, one of the most genuinely creepy places in existence--the only scenes actually shot on location rather than in Lawrence, Kansas.

Despite a few amateurish performances and some obvious cost-cutting (like a few out-of-sync footsteps on the sound track), Carnival of Souls is such a fascinating and nightmarish ride with so much somber, poetic imagery that it strikes a chord in our subconscious and is impossible to forget. Even though she is dislocated from reality for most of the movie, Mary Henry is a character with whom we somehow identify, perhaps because of our own deep-seated fears of the unknown and uncertainty about death. The direction creates an astonishing, captivating flow, surpassing a modern "blockbuster" like The Sixth Sense in a completely unlabored and unselfconscious way. Even the seemingly trite inclusion of unpleasant, persistent attentions by Mary's lecherous, voyeuristic neighbor parallels the relentlessness of her unearthly visions, further highlighting her alienation and heightening the claustrophobic, haunted atmosphere; it also adds a dangerous sense of potential sexual violence. For those who love fright films that promote thought as well as shivers, I can't recommend Carnival of Souls highly enough. It is the best and most gripping representative of its sub-genre.

The film's history is almost as odd as the film itself. It is the only theatrical film ever made by director Herk Harvey, who was largely employed making industrial films for the Centron Corporation of Lawrence, Kansas. Harvey and writer John Clifford evolved the idea for the film in 1961 and raised a meager $30,000 from private investors in Lawrence where most of the film was shot. The results are the best $30,000 ever spent on a film. It is unsettling, moody, and seeps into the psyche of the viewer. Most fright films made for several hundred times that amount don't begin to approach its effectiveness. The production team was financially naive, however, and signed a crooked distributor, Herts-Lion, to market Carnival of Souls. After its premiere in Lawrence, it was generally consigned to a low-end double-bill, mostly at drive-ins, with the mediocre Devil's Messenger; the distributor shortened it by five minutes. Herts-Lion went bankrupt and disappeared; its check to Harvey bounced and Harvey's investors lost their money. But, as Harvey explained, the investors never had any hard feelings or regrets.

With most low-budget films, that would be the end of the story. However, not long after the debacle of its initial release, Carnival of Souls was sold to independent TV stations and began to develop a sizable cult following. Its haunting images inspired George Romero, whose legendary 1968 independent film Night of the Living Dead it resembles visually: in a sense, little Carnival of Souls is the direct progenitor of an entire sub-genre. In 1987, Harvey made plans for a theatrical revival of his original, uncut version, and it was very well-received. The film has never been out of print on VHS and DVD since that revival. Unfortunately, the prints used for these home video releases seem to stem largely from the abbreviated Herts-Lion version that found its way to TV, and are often in deplorable video and audio quality. In 2000, the Criterion Collection changed that sad state of affairs with a gorgeous 2-DVD release of both the short and original director's versions. (Incidentally, in 1998, Wes Craven and company made a completely unrelated, generally poor film with the same title.)

If you love this film, it is worth spending a typical sale price of about $25 for the 2-DVD Criterion set. The first disc contains the shorter 78-minute Herts-Lion version, digitally restored from the best surviving element, a duplicate negative. The results are breath-taking. Except for a few scratches, it looks brand new, with unbelievable clarity, contrast, and detail. It is unlikely that the film makers ever saw the film in quality like this. Also included are a documentary, outtakes accompanied by Gene Moore's organ score, the theatrical trailer, a history of Saltair, and notes on the film's locations.

The original 83-minute Director's Version, as revived theatrically in the late 1980s, appears on the second disc. Elements as pristine apparently no longer exist for this version and the transfer, although quite fine, is not as spectacular as the abbreviated edition on the first disc. The complete version contains interesting periodic commentary by the director and writer drawn from interviews recorded at the time of the theatrical revival (Herk Harvey died in 1996), an hour of excerpts from the industrial films made by the Centron Corporation for which Herk Harvey worked, and printed interviews with illustrations. Both versions are subtitled in English for the hearing impaired. Although the complete film's state of preservation is less brilliant than the restored cut version on the first disc, it is invariably to be preferred: the restored five minutes of expository and reflective material--numerous deletions made by Herts-Lion, from individual shots to brief scenes--clarify or deepen character motivation, intensifying the rhythm of the film. One of Criterion's best releases, the set is invaluable to admirers of the film.

Review by Robert E. Seletsky

| Released by Criterion Collection |

| Region 1 NTSC |

| Not Rated |

| Extras : see main review |